YOUR CART

- No products in the cart.

Subtotal:

$0.00

BEST SELLING PRODUCTS

Pioneer Women was created in the United States in 1925 to help the pioneering women’s cooperatives in then Palestine through American-based philanthropic efforts, serving as a channel for working class Jewish immigrant women who sympathized with aims and ideals of their sisters involved with the labor movement in Palestine to feel as if they were invested in this work. It also provided a supportive platform for Zionist leaders pre-World War 2, before the cause of a burgeoning State of Israel became an integral component to American Jewish consensus.

The early struggle for gender equality by halutzot – women pioneers – in Israel is not a story often told. Let’s consider the three major waves of aliyot to Israel prior to the War of Independence in 1948. The majority of settlers in the first Aliyah in the 1880s and 1890s were religious Zionists who came as families in hopes of cultivating the land and hastening the coming of Mashiah (the messiah). To be sure, the lives of Central and mostly Eastern European Jewish women who immigrated with their husbands and children during this wave did change in their new environment, but, by and large, they were committed to maintaining home and family as before – imagine if Tevye and Golda had left Anitevka for Palestine instead of New York. Interestingly enough, it was eye opening to these Ashkenazi women how much more subservient Yemenite women were in religious society. A few distinguished women of that era began to question their roles and write about it, but striving for gender equality was not on their radar.

The early struggle for gender equality by halutzot – women pioneers – in Israel is not a story often told. Let’s consider the three major waves of aliyot to Israel prior to the War of Independence in 1948. The majority of settlers in the first Aliyah in the 1880s and 1890s were religious Zionists who came as families in hopes of cultivating the land and hastening the coming of Mashiah (the messiah). To be sure, the lives of Central and mostly Eastern European Jewish women who immigrated with their husbands and children during this wave did change in their new environment, but, by and large, they were committed to maintaining home and family as before – imagine if Tevye and Golda had left Anitevka for Palestine instead of New York. Interestingly enough, it was eye opening to these Ashkenazi women how much more subservient Yemenite women were in religious society. A few distinguished women of that era began to question their roles and write about it, but striving for gender equality was not on their radar.

It was the second Aliyah (1904-1914) – that took place before World War I and the third Aliyah that took place immediately after World War I that Palestinian Jewish women’s suffrage took hold and began to make its mark in profound ways. These aliyot groups were comprised mainly of young single people who had been influenced by social and radical movements in Russia and Poland that had begun to flower at the end of the 19th century. Different kinds of relationships and expectations began to develop because of these revolutionary movements – think about Perchik and Tzeitle in Fiddler on the Roof.

Worth noting is that only one in ten olim in the second Aliyah were women – most were idealistic men. We can imagine that the small percentage of women that did go were also idealistic, brave, and motivated, expecting to work side by side with their male counterparts. Most of the Jewish farming that was happening in Israel at the time was being done by the religious Zionists of the first Aliyah who resented the secularity of these new halutzim (pioneers). They had no idea how to deal with these women demanding equality and participation in the hard labor. While no one had an easy time, these committed women were very disappointed and frustrated. Even when the new halutzim began creating independent farms in the north, starting a community from scratch so the gender role “playing field” should have been level, it was not. Women were again relegated to cooking, laundry and cleaning, and not permitted to join these farms as full members because the understanding was that they lacked the physical strength to be of value in the fields.

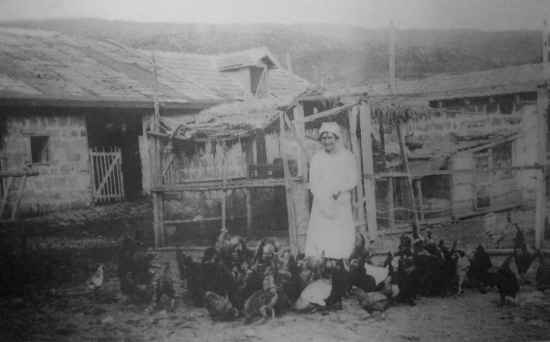

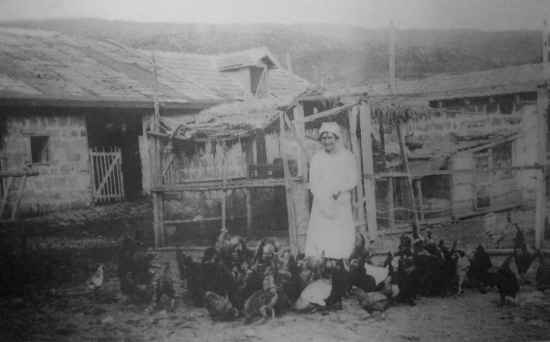

Because of the painful gap between the expectations of the second Aliyah women and the realities they encountered, the Kinneret Farm – the first woman’s training farm for agricultural workers – was established in 1911, largely due to the efforts of Russian born Hannah Meisel who immigrated with an agricultural degree in hand. Kinneret Farm trained women to work in branches of agriculture that played to their strengths, such as livestock, dairy agriculture, and the growing of vegetables. It also became the initial focal point for women’s political organizing in Palestine.

Graduates of the program went off to start their own collectives or joined with men to start mixed-gender farms. While progress was slowly being made, the third Aliyah, which was 36% women, gave the cause of women workers a boost. This new crop of women were prepared physically and psychologically, with the same skills as their male counterparts, and they came ready to work together.

Still, for women, the situation was not ideal, so when the Histradrut was formed as the umbrella workers organization in 1920, halutzot (women pioneers) were divided about whether to enter the organization as a special sub-unit or play their part in existing mixed workers’ groups and parties. But when only 4 of the 87 chosen delegates for the first Histadrut council were women, that the initiative for separate women’s representation was revived and the Woman’s Workers Council was set up in 1921. This is where the story of Mo’ezet Hapoalot (General Council of Women Workers in Palestine) and Pioneer Women formally begins.

Mo’etzet Hapoalot represented the interests of both women workers and the wives of male Histradrut members. It championed women’s pursuit of suffrage and equality (including in political office), trained women in urban-industrial and rural-agricultural work and managed corps of volunteers and welfare organizations.

It’s founder, Ada Fishman Maimon (a proud descendant of the Rambam/Maimonides), known as one of the spiritual mothers of Jewish feminism in Israel, was born in Bessarabia (Romania) in 1893 in a religious Zionist home and emigrated to Palestine in 1912 during the 2nd Aliyah. Her brother, Rabbi Yehudah Leib Maimon, was a key figure in the Mizrahi religious Zionist party. Ada devoted her life to the feminist cause and to improving the status of working women. She founded Moetzet Hapoalot and served in the Mapai Party in the first and second Knessets (Israeli legislature). She worked tirelessly on behalf of women’s suffrage. She published many compelling calls for equality in both the secular and religious realms. She would not accept the fact that ultra-Orthodox men would leave a room when she entered to attend a meeting. Maimon and her followers did what they could to put women’s economic and civil equality on the national agenda. Her missions included professional training for women pioneers, mainly in agriculture and industry, the widening of job options and the establishment of an education system for young children that would allow mothers to go out of the home to work. She would travel from Kibbutz to Kibbutz and farm to farm to teach women to organize for themselves for better pay and independent rights like being able to own property and having personal agency to send for more European family.

In 1925, the year the Pioneer Women’s Organization of America was founded by another remarkable Jewish feminist, Sophie Udin and six other dynamic women, the founding committee of Moetzet Hapoalot disbanded because of conflicts within the party. In 1928, Golda Meyerson (Meir) was installed as the secretary general of Moetzet Hapoalot. But people were so upset that Maimon had been pushed out that Golda was forced to resign in 1930. Maimon’s supreme goal was a comprehensive “change of values” which consisted of equality in all walks of life between women and men. In a letter to a friend, she wrote: “As far as I am concerned, the question of women’s liberation in work and so on is an international issue. For one major issue pains and insults women all over the world.” She continued to represent women (both Jewish and Arab) of Palestine and later Israel, at international women’s conferences throughout her life.

Sophie Udin was born in Ukraine in 1896 and emigrated to Pittsburgh as a young girl with her socialist parents. She became active in the American branch of the Poale Tzion (Zionist Workers) movement. Brilliant and driven, she received both undergraduate and graduate degrees in Library Science from Columbia University. In 1922, she married Poale Zion officer Pinhas Ginguld who was, at the time, head of a network of secular Yiddish folk schools and a Teacher’s Seminary in New York City. During her time specializing in foreign collections at the New York Public Library, she spent three years in Palestine, all before her 30th birthday, to help set up the Jewish National and University Library. Among her many contributions there, she convinced the director to adopt the Dewey Decimal System and Anglo-American cataloging. She also secretly worked for the Haganah.

Sophie had a knack for raising American funds to support a range of Zionist causes including literacy, education, defense, and women workers. With the assistance of six wives of Poale Zion members, in response to some needs of women working in a nursery near Jerusalem, Sophie founded the Pioneer Women’s Organization of America, which was incorporated in December of 1925. At their first convention in 1926, Leah Biskin was elected as their national president and the following organizational goals were articulated:

1 – To help create a homeland in Palestine based on cooperation and social justice

2 – To give moral and material support to Mo’etzet Hapoalot

3 – To educate American Jewish Women about taking a more conscious role in the establishment of a better and more just society in America and around the world.

At the outset they mobilized 20 clubs of 900 women* initially comprised of Yiddish speaking immigrant women who were idealistic and committed to supporting the flourishing of girl’s agricultural training schools in cities most of them never expected to see for themselves. In 1939, the group’s name was formally shortened to Pioneer Women. Of course, these two extraordinary women never acted alone – they worked with teams of hard-working women driven to contribute to the building of a Jewish homeland, both on the ground and from afar.

From the beginning, and set apart from other Jewish women’s organizations, Pioneer Women remained true to Jewish immigrant values of maintaining Yiddishkeit, class consciousness, feminism, and cultural identity, intentionally not succumbing to bourgeoise trappings of American social climbing and consumerism.

In 1981, Moetzet Hapoalot changed its name to NA’AMAT – an acronym for Nashim Ovdot u’Mitnadvot – Nun, Ayim, Mem, Tav – literally “Working and Volunteering Women”. Today, with a new tagline of “Tnuot Nashim L’Israel” – “Women’s Organization of Israel” – NA’AMAT Israel remains the largest women’s movement in Israel with a membership of over 300,000 Jews, Arabs, Druze and others representing the entire spectrum of Israeli society with 100 branches in cities, towns and settlements all over the country. Also in 1981, the United States Pioneer Women changed its name to NA’AMAT USA to reflect their ongoing close ties and shared mission.

Although agriculture has long since taken a back seat to high-tech, education, defense industries, and the like, Israeli women are still working as hard as ever for equal rights, education, and respect, and we cannot overstate the essential role that Pioneer Women played and NA’AMAT continues to play in supporting the needs of women, youth, and families of all stripes in Israel whose myriad contributions are essential to a thriving state.

There is no doubt that Israel’s current coalition government which is openly dedicated to regressive practices of suppressing the rights of women and marginalized populations and denying Jewish identity to those who express their Zionism in different ways would be horrifying to Ada, Sophie, and the thousands of women that worked with them during their mission-driven lives. Hard work and coalition-building is still needed in the fight for equality writ large in our beloved homeland. We members and supporters of NA’AMAT, like our mothers, grandmothers, and great grandmothers before us, are ready to roll up our sleeves and meet these current and future challenges head-on.

*Ida Katz, Rabbi Tilchin’s grandmother, was always proud of the fact that she was a member of Club 1.

Compiled and edited by Rabbi Marcia Tilchin and Susan Seely.